The site for writers of all genre, and the readers who love them. Find what you want to know.

Point of view (POV)

Point of view (literature) or narrative mode, the perspective of the narrative voice; the pronoun used in narration. Narration is the use of a written or spoken commentary to convey a story to an audience. Narration is conveyed by a narrator: a specific person, or unspecified literary voice, developed by the creator of the story to deliver information to the audience, particularly about the plot: the series of events. Narration is a required element of all written stories (novels, short stories, poems, memoirs, etc.), presenting the story in its entirety. It is optional in most other storytelling formats, such as films, plays, television shows and video games, in which the story can be conveyed through other means, like dialogue between characters or visual action.

Narration

Narration is the art of using written or spoken commentary to communicate a story to an audience. It is delivered by a narrator, who may be a specific character or an unnamed literary voice crafted by the story’s creator to provide the audience with vital information about the plot, which consists of the sequence of events. In written stories such as novels, short stories, poems, and memoirs, narration is an essential element that presents the narrative in its entirety. However, in other storytelling formats like films, plays, television shows, and video games, narration is often optional as the story can be effectively communicated through dialogue or visual action.

The narrative mode, which often overlaps with the concept of narrative technique, includes various choices that a creator makes in developing their narrator and narration. These choices encompass the narrator’s point of view, the grammatical person that determines the relationship between the narrator and the audience, and the narrative tense, which indicates whether the story unfolds in the past or present. Additionally, narrative techniques involve methods for establishing the setting, developing characters, exploring themes, structuring the plot, selectively revealing information, adhering to or challenging genre conventions, and employing specific linguistic styles alongside other storytelling devices.

Therefore, narration encapsulates who tells the story and the manner in which it is articulated, whether through techniques such as stream of consciousness or unreliable narration. The narrator can be anonymous, a character within their own tale, or even the author themselves, and may recount events without being directly involved in the plot, possessing varying degrees of insight into characters’ thoughts and distant occurrences. Certain narratives feature multiple narrators to weave together the experiences of different characters across various timelines, resulting in a richly layered perspective.

First-Person

A first-person point of view reveals the story through an openly self-referential and participating narrator. First person creates a close relationship between the narrator and reader, by referring to the viewpoint character with first person pronouns like I and me (as well as we and us, whenever the narrator is part of a larger group).

Second-Person

The second-person point of view is a point of view similar to first-person in its possibilities of unreliability. The narrator recounts their own experience but adds distance (often ironic) through the use of the second-person pronoun you. This is not a direct address to any given reader even if it purports to be, such as in the metafictional If on a winter’s night a traveler by Italo Calvino. Other notable examples of second-person include the novel Bright Lights, Big City by Jay McInerney, the short fiction of Lorrie Moore and Junot Díaz, the short story The Egg by Andy Weir and Second Thoughts by Michel Butor. Sections of N. K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season and its sequels are also narrated in the second person.

You are not the kind of guy who would be at a place like this at this time of the morning. But here you are, and you cannot say that the terrain is entirely unfamiliar, although the details are fuzzy.

Third-Person

Writing in the third person means the narrator is an outside observer referring to characters by their names or third-person pronouns such as he, she, it, they, him, her, them, and so on. This perspective is commonly used in both creative and academic writing to establish distance and objectivity.

Types of Third-Person POV

There are three main types of third-person point of view, each offering a different level of access to the characters’ internal worlds:

- Third-person omniscient: The “all-knowing” narrator has a god-like perspective, access to the thoughts and feelings of all characters, and can move freely through time and location. This style is common in classic literature, such as the works of Charles Dickens and Jane Austen.

- Third-person limited: The narrative is restricted to a single character’s perspective at a time. The reader only knows what that specific character knows, sees, and thinks, creating a close, intimate connection without using “I” pronouns. This is a popular approach in modern fiction, including the Harry Potter series.

- Third-person objective: The narrator is a neutral, “fly-on-the-wall” observer who only describes events and dialogue without delving into any character’s thoughts or feelings. This style is similar to a news report and is used to allow readers to draw their own conclusions based on observable actions.

Alternating / Multiple

While the tendency for novels (or other narrative works) is to adopt a single point of view throughout the entire novel, some authors have utilized other points of view that, for example, alternate between different first-person narrators or alternate between a first- and a third-person narrative mode. The ten books of the Pendragon adventure series, by D. J. MacHale, switch back and forth between a first-person perspective (handwritten journal entries) of the main character along his journey as well as a disembodied third-person perspective focused on his friends back home.

“I’ll tell you what I’ll do,” said the smith. “I’ll fix your sword for you tomorrow, if you tell me a story while I’m doing it.” The speaker was an Irish storyteller in 1935, framing one story in another (O’Sullivan 75, 264). The moment recalls the Thousand and One Nights, where the story of “The Envier and the Envied” is enclosed in the larger story told by the Second Kalandar (Burton 1: 113-39), and many stories are enclosed in others.”

What Is Head-Hopping?

A look at the problem with head-hopping when you write from Writers Write. Head-hopping occurs when we change viewpoint (or point of view) in the middle of a scene. The rule is that you only have one viewpoint in a scene. When we write fiction, we write it from a specific viewpoint. In most fiction we read through the eyes of the protagonist and one or two other characters. Carefully chosen viewpoint characters help you avoid confusing readers.

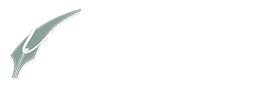

The Mechanisms of Point of View

You may find this article nerdy, maybe even pointless, because why should a writer dismantle the POV clockwork and not adopt a common one, like first- or third-person, past or present, distant, or limited? The answer: Understanding the nuts and bolts of POV enables you to find opportunities to innovate and push the envelope of narrative.

Pop Quiz: Who Are You?

Shirley Jump

When I first started writing, I thought I wanted to be the next Jane Pauley. I could just see myself, leaping after the big story, landing the big headlines and the cheers of the newsroom. Then, after a few years at a city newspaper, I realized I didn’t have what it took to be an investigative reporter. I didn’t like butting into people’s lives, I didn’t like stirring up trouble and I especially didn’t like hunting down a story that didn’t want to be found.

Knowing and Finding Your Voice

By Shirley Kawa-Jump

Finding your true writing voice is a lot like falling in love — you know it when it happens. Until then, you bumble along, trying this style and that, wondering if this is it or if a better voice is out there just waiting for you. You question and doubt, reaching nearly the point of despair before finally, your true voice comes to you and you know exactly who you are as a writer.

Writing Romantic Comedy

by Shirley Kawa-Jump

Quick — tell a joke. On paper, in the beginning of a novel. Then hope that a few thousand readers will not only get the joke, but remember you as a funny writer. Then repeat that for the next 400 pages, all while juggling plot, realistic characters and enough conflicts to fill a church. Sound difficult? It is, as anyone who has tried to write comedy will tell you.

Everything You Always Wanted to Know About POV

by Kathy Carmichael

Kathy offers a monthly question and answer blog that presents a subscriber’s question and answers offered by other subscribers or by Kathy herself. There is plenty of great advice here for the writer to glean.