The site for writers of all genre, and the readers who love them. Find what you want to know.

The Mechanisms of Point of View

By: Stefan Emunds

www.eightcrafts.com

You may find this article nerdy, maybe even pointless, because why should a writer dismantle the POV clockwork and not adopt a common one, like first- or third-person, past or present, distant, or limited?

The answer: Understanding the nuts and bolts of POV enables you to find opportunities to innovate and push the envelope of narrative.

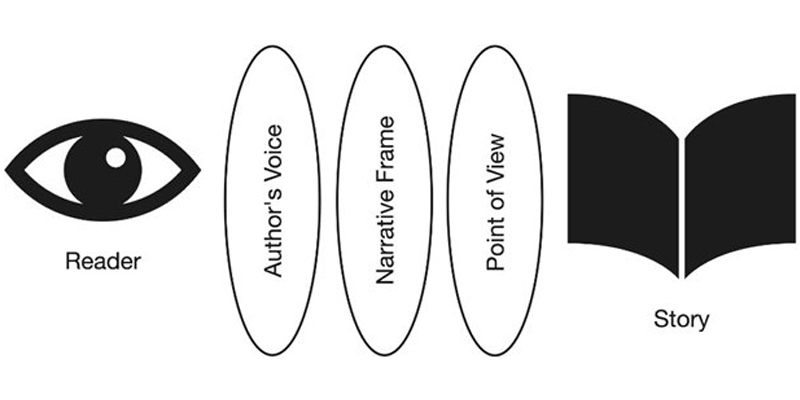

1 The Three Reading Lenses

Readers read stories through three lenses:

- The author’s voice

- A narrative frame

- Point of Views, POVs

2 The Author’s Voice

Amy Tan said the author’s voice is the result of her experiences, attitudes, habits of thinking, and the way she expresses herself.

Neil Gaiman calls the author’s voice attitude and soul and says that while stories may have different languages and feelings, the soul doesn’t change.

Paulo Coelho combines distant third-person narrative with conversational-lyrical prose. Charles Dickens had a baroque writing style and made use of a wide array of rhetorical devices. Stephen King’s voice is plain, but he gets poetic and symbolic when he reveals the dark sides of his characters.

Young writers are prone to imitating other authors’ voices. There is nothing wrong with that, but writers are born with their own voices. Your voice is like a seed that you plant in the garden of your writing. If you keep removing the weeds, it will grow into a tall and beautiful tree.

3 The Narrative Frame

In its simplest form, the narrative frame is a story’s wrapping or casing, like the frame of a painting.

Examples: epistolary novels and fictional diaries.

Narrative frames can assume functions. For example, they can determine who tells the story, to whom, and why.

In the case of Alias Grace, the narrative frame is a psychological evaluation. Illuminae’s narrative frame is a file that contains classified reports, like emails, videos, and interviews. The Museum of Innocence takes the reader on tour through the protagonist’s museum of memories.

In The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Watson is both the narrative frame and the POV character. When a narrative frame overlaps with a POV character, we have a frame narrator.

4. The Point of View, POV

An author can silence her voice and dispense with a narrative frame, but she can’t avoid POV. Hence, readers never get direct access to a story. They need to endure (or enjoy) the POV’s subjective take of a story.

To give you an allegory, the author’s voice compares to

the movie script, the narrative frame to the movie director, and the POV to the cameraman. To understand POV choices, let’s run with the camera allegory.

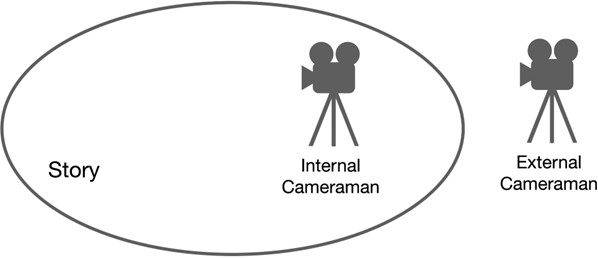

4.1 Story-external and Story-internal POVs

The cameraman can be outside or inside the story.

If the cameraman is outside the story, the POV takes the form of a narrator, either the author or an external frame narrator. The narrator’s voice is palpable, and the reader enjoys a bird’s-eye view of the story.

In The Nazarene by Sholem Asch, the frame narrator is Pan Viadomsky, who tells a Jewish scholar what happened in his past life as a Roman officer in Jerusalem at the time of Jesus.

4.2 POV Distances

If the cameraman is outside the story, the POV is always distant. If the cameraman is inside the story, writers can choose from the following narrative distances:

Distant: The cameraman is at the inner periphery of the story, for example, a frame narrator who was or is involved in the story. Examples: The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes and Gates of Fire. In Gates of Fire, Xeones, one of the three survivors of the Battle of Thermopylae, tells the story to the Persian king’s

- Mid-distant: The cameraman follows POV characters like a cameraman films a movie. They focus on characters, but they also show some of what’s going on around

- Limited (aka subjective): The cameraman films over the characters shoulder and shows only what the POV character sees, hears, smells, tastes, and touches.

- Examples: Harry Potter and epic fantasy novels à la Brandon Sanderson.

- Deep (aka subjective): The camera is inside the characters’ head. Example: Hunger Games and Paladins of Souls.

- Limited and deep POV restrict readers to the POV of characters, and the action is immediate and

The differences between limited and deep are subtle. Deep POV is a bit more immediate than limited POV, shows more and tells less, and the narrative disappears into the story (no filter words).

The following paragraph is in limited POV:

Simon heard cars approaching the house. He peeked through the gap between the curtains. An army jeep stopped in front of the house, and an SS officer stepped out. “Oh, God, oh God, oh God.”

We have a filter word (heard) and a tell (approaching). The same paragraph in deep POV:

The gravel on the driveway crackled. Simon peeked through the gap between the curtains. An army jeep stopped in front of the house, and an SS officer stepped out. “Oh God, oh God, oh God.”

When should a writer choose limited or deep POV? It depends on how hard she wants to work. The more immersive, the better. For most genres, for example fantasy, a limited POV suffices because readers are most interested in the story world and the magic system. However, in the case of literary fiction, deep POV may be the better choice.

As a writer, you are free to move closer to and away from the action. Just be aware that, in art, freedom is a two-edged sword.

4.3 POV Knowledge

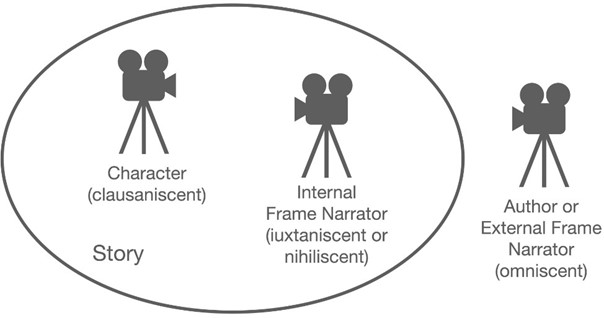

Apart from showing the action, written stories can take readers into the head and heart of a character. POVs can be omniscient, iuxtaniscent, clausaniscent, and nailset.

- Omniscient: The cameraman knows everything, all exposition and backstory, the future, and the characters’ thoughts, dreams, emotions, and feelings.

- Iuxtaniscent: The cameraman knows parts of exposition and backstory, and some of the characters’ thoughts and feelings.

- Clausaniscent: The cameraman is a frame narrator or story character and only knows what they know.

- Nihilniscent* (aka objective or dramatic POV): The cameraman knows nothing, films the events as they unfold, and doesn’t reference thoughts and feelings. *Coined for the sake of this article

In the case of omniscient and iuxtaniscent, the cameraman uses a second psychic camera with which she films characters’ thoughts, emotions, and feelings.

In limited POV, this can look like (thought in italics): Simon heard cars approaching the house. He peeked through the gap between the curtains. An army jeep stopped in front of the house, and an SS officer stepped out. “Oh God, oh God, oh God. My days are numbered.”

In the case of deep POV, the internalizations of the POV character disappear into the narrative: The gravel on the driveway crackled. Simon peeked through the gap between the curtains. An army jeep stopped in front of the house, and an SS officer stepped out. “Oh God. oh God. oh God.” His days were numbered.

While deep POV is more immersive than Limited POV, Limited POV makes it easier to reveal subtext. Since the limited cameraman is not in the POV characters head, but looks into it, she could capture unconscious

thoughts or thoughts the POV character can’t articulate (yet).

4.4 Narrative Distances, Immersion, and Empathy

Sympathy antonym antipathy) means getting attached to characters. Empathy (no antonym) is experience – immersive. Readers don’t empathize with a POV character if she isn’t doing anything. But as soon as her boyfriend breaks up with her, she goes into labor, or someone tries to kill her, empathy kicks in.

A POV character is only the vehicle that enables readers to empathize with story experiences.

Empathy = Story

However, intelligent characterization can boost empathy. For example, it’s scarier when a twelve-year-old girl faces a grizzly bear than a seasoned hunter.

An author allows/disallows empathy through her use of POV. Limited and deep POV immerse readers and enable empathy. Conversely, distant, and multiple POV dilute empathy.

In Perfume, Patrick Süskind plays with that. In the opening, he tells his readers that the protagonist is a beast of a man but makes him sympathetic a few chapters later. He even takes his readers into the protagonist’s POV, conjuring empathy. Then, he pulls his readers out and takes them all the way back to antipathy.

Some genres, for example, epic fantasy, require multiple POVs to convey exposition and backstory. A fantasy author needs to balance empathy with the use of multiple POVs. For those reasons, fantasy authors like to write in multiple limited POVs.

4.5 POV Pronouns

You can choose from three POV pronoun scenarios:

- First-person

- Second-person

- Third-person

Third-person adds distance to the narrative, but it is possible to write in limited or even deep third-person POV.

Deep first- and third-person are almost identical, and the writer can switch between the two by swapping pronouns (changing I to he or she).

Second person POV breaks the fourth wall. The narrator addresses the reader as if she were a story character and pulls her into the story. Example: If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler.

Second-person POV disables empathy because there is no POV character to identify with, but it boosts tension since story events trigger readers’ emotions directly:

Third-person: He dumped me on my wedding. Vs. Second-person addressing the reader: How could you dump me on our wedding?

4.6 Switching Cameramen

The camera isn’t exclusive to the protagonist, and other characters can grab it too. You know this as multiple or selective POV.

As long as you don’t switch cameramen within scenes, the so-called head-hopping, you can do as you see fit. For example, if you want your reader to know both sides of a love relationship, you can write your romance in dual POV. Also, you can switch between first- and third-person (Love You More) and between distant and limited/deep POV.

4.7 POV Reliability

Unreliable means the author, frame narrator, or POV character may withhold information or even lie.

Reasons for using unreliable narrative:

- It produces complex and interesting POV

- It creates mystery. Readers figure that the POV character is hiding things and read on to find out what that might be.

- It allows readers to keep a distance from the otherwise empathic story Example: Lolita.

Mind that, at the end of the day, every narrator is unreliable, even the author.

4.8 Narrative Time Management

A writer can choose to write her story as if it were in the past, present, future, or move back and forth in time.

Past and future tense add distance to the narrative. Present tense reduces distance and makes action more immediate.

One could make the argument that deep POV should come with the present tense. See for yourself:

The gravel on the driveway crackled. Simon peeked through the gap between the curtains. An army jeep stopped in front of the house, and an SS officer stepped out. “Oh God, oh God, oh God.” His days were numbered.

Vs.

The gravel on the driveway crackles. Simon peeks through the gap between the curtains. An army jeep stops in front of the house, and an SS officer steps out. “Oh God, oh God, oh God.” His days are numbered.

Suzanne Collins wrote Hunger Games in present-tense deep POV.

4.9 POV Comments

If the author gives the cameraman a microphone, she can comment on story events. This is old-school.

Nowadays, authors tend to refrain from commenting on stories and let the readers judge for themselves.

Exceptions: intentional author intrusions. Intentional author intrusions can be pretty cool if they are fresh and serve a purpose.

5. POV Choices

A POV is a combination of the POV choices cataloged above: internal/external, POV distances, POV knowledge, POV pronouns, single/multiple POV, POV reliability, narrative time management, and narrative comments.

These choices give writers a few hundred POV combinations to choose from. Most don’t make sense. Or do they?

Let’s have a look at a few common POV choices:

Distant Third-person Omniscient: The cameraman is external and has a psychic camera to film characters’ thoughts and feelings. Example: War and Peace and Tale of Two Cities.

Limited Third-person Past Tense: The cameraman is a story character, usually the protagonist. Example: Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.

Deep First-person Past Tense: The camera is inside the head of the protagonist. Example: The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time.

Multiple Limited Third-person Past Tense: Multiple story characters grab the camera. Example: Words of Radiance.

Third-person Nihiliscent: The cameraman is inside the story but lacks the psychic camera. Example: The Lottery by Shirley Jackson.

Let’s have a look at a few unusual POV choices:

The Book Thief: The narrator is Death (a frame narrator), and the POV is first-person omniscient.

Gone Girl: Unreliable dual first-person POV, alternating between past and present tense.

The Night Circus: Distant third-person omniscient laced with second-person.

An almost impossible POV is limited third-person omniscient. Limited means that the cameraman is a story character. A story character can’t be omniscient, except when she is God.

6. How to Choose a Narrative Frame and POV for Your Story

To find the optimal narrative frame and POV for your story, you can get inspirations from other authors and/ or ask yourself the following questions:

- What do I want to highlight, the genre, the theme, or the protagonist’s perspective, and which POVs help me with that?

- What kinds of POV do my readers prefer?

- What are the POV conventions of my story’s genre?

- How much do I want to immerse my readers?

Margaret Atwood recommends deciding for whom you write your story and what you want to tell them before choosing a POV.

Amy Tan suggests writing your opening in different POVs and seeing where that takes you.

If you are a young writer, stick with common POV choices, but you may want to add a cool narrative frame. If you feel you’re ready to innovate, by all means, do so. Readers love innovations, and you may end up inspiring other authors.

AGENTS & EDITORS

- Agents: Knowing When To Hold One and When To Fold

- Copyright Primer, Know Your Rights

- Getting Offers from Multiple Literary Agents

- Landing An Agent Elements Of A Winning Query

- Literary Agents List

- Preditors and Editors

- Publishing, Writing Terms, Acronyms

- Tips for a Successful Editor Appointment

- Want More? Here’s How to Get It

- What NOT to Do When Beginning Your Novel

- Windup for the (Story) Pitch

- Write the Perfect Book Proposal

CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS

![]()

CALLS FOR SUBMISSIONS MAIN PAGE

- 2026 FEB Calls for Submissions

- 2026 JAN Calls for Submissions

- 2025 DEC Calls for Submissions

- 2025 NOV Calls for Submissions

- 2025 OCT Calls for Submissions

- 2025 SEP Calls for Submission

- 2025 AUG Calls for Submission

- 2025 JUL Calls for Submission

- 2025 JUN Calls for Submission

- 2025 MAY Calls for Submission

- 2025 APR Calls for Submission

- 2025 MAR Calls for Submission

- 2025 FEB Calls for Submission

CHARACTERIZATION

CONFLICT

DIALOGUE

GRAMMAR & FORMATTING

![]()

GRAMMAR & FORMATTING MAIN PAGE

- Achieving 250 Words / 25 Lines Per Page

- And Sammy, Too? Oh, No!

- Changing Double Hyphens to EM Dashes in Word

- Edit Easier

- High Hopes–Avoiding Common Mistakes

- Misused Words

- Navigating In Your Novel

- Proofreaders Marks

- Research Links

- Rules for Writers

- Slang and Jargon Souces

- Tightening Your Manuscript and Trimming the Word Count

JOBS / MARKETS

- 3 Ways to Make Your Non-Fiction Article Pitch Stand Out

- 35 Online Work Ideas to Earn Good Money Whilst Studying

- An Interview with Holly Ambrose

- Beyond the Basics

- Copyright Primer, Know Your Rights

- Finding Markets Fiction and Nonfiction

- Freelance Writing 101

- Getting Offers from Multiple Literary Agents

- How To Market Your Book After You’ve Written It

- How to Write a Novel Synopsis

- How To Write Your Own Press Releases

- Magazine Links

- Making Money As a Corporate Freelancer

- Market News–All Genres

- Need a Clip? Open a Newspaper

- Newspaper Writing Resources

- Publisher’s Websites

- Selling to Children’s Markets

- Submitting to UK Markets

- Syndication 101

- the Power of the Press

- To Specialize, or Not to Specialize?

- Ultimate Guide to Being a Freelancer 2025 Update

- What Are Your Chances of Getting Published?

- Why Article Writing Should Be A Part Of Your Career Development Strategy

- Why E-Books?

- Write the Perfect Book Proposal

- Write Your Way to $1000 a Month

- Youth Writing Markets

PLOTTING

- 3 Ways to Know When to End Your Chapters

- 7 Excellent Plotting Tips from Agatha Christie

- 7 Ways to Add Great Subplots to Your Novel

- 8 Best Writing Tips to Become a Best Storyteller

- Does Your Plot Need a Subplot?

- Love to Write: Here Is How You Can Build Your Career

- Slang and Jargon Souces

- The All Purpose Plot

- Turning Points and Plot Points in Storytelling

- What NOT to Do When Beginning Your Novel

- Writing the Novel by the Numbers

POINT OF VIEW

QUERIES & PROPOSALS

- Agents: Knowing When To Hold One and When To Fold

- Getting Offers from Multiple Literary Agents

- How to Write a Novel Synopsis

- Landing An Agent Elements Of A Winning Query

- Path to Self-Publishing Success

- Publisher’s Websites

- Publishing, Writing Terms, Acronyms

- Science & Science Fiction Writing Organizations

- Submission Tracking

- Surviving a Book Proposal

- Windup for the (Story) Pitch

- Write the Perfect Book Proposal

- Writing a Synopsis & Query Letter

SUBMISSIONS

- Agents: Knowing When To Hold One and When To Fold

- An Interview with Jack Fisher

- Copyright Primer, Know Your Rights

- EBooks-Fears to Possibilities

- How to Write a Novel Synopsis

- Literary Agents List

- Path to Self-Publishing Success

- Publisher’s Websites

- Publishing, Writing Terms, Acronyms

- Science & Science Fiction Writing Organizations

- Selling to Children’s Markets

- Submission Tracking

- Surviving a Book Proposal

- What Are Your Chances of Getting Published?

- Write Your Way to $1000 a Month

- Writing a Synopsis & Query Letter

- Youth Writing Markets

SYNOPSIS

TIP SHEETS & GUIDELINES

![]()

TIP SHEETS & GUIDELINES MAIN PAGE

- Achieving 250 Words / 25 Lines Per Page

- Changing Double Hyphens to EM Dashes in Word

- Copyright Primer, Know Your Rights

- How To Write Your Own Press Releases

- Knowing and Finding Your Voice

- Plan for Success

- Publisher’s Websites

- Science & Science Fiction Writing Organizations

- What NOT to Do When Beginning Your Novel

- Why E-Books?

- Working with a Critique Group

WORKSHOPS & CONFERENCES

WRITING CONTESTS

![]()

ABOUT WRITING CONTESTS

- A Guide to Assessing Writing Contests

- Writer’s Conferences Do You Really Need To Attend?

- Writing Groups List

- 2026 FEB Writing Contests

- 2026 JAN Writing Contests

- 2025 DEC Writing Contests

- 2025 NOV Writing Contests

- 2025 OCT Writing Contests

- 2025 SEP Writing Contests

- 2025 AUG Writing Contests

- 2025 JUL Writing Contests

- 2025 JUN Writing Contests

- 2025 MAY Writing Contests

- 2025 APR Writing Contests

- 2025 MAR Writing Contests